In the spring of 1945, Europe breathed again — but in the footsteps of the Allied armies, that breath of freedom mixed with the smell of ashes and death.

Behind the retreating enemy lines, they discovered places that no one could have imagined, landscapes of industrial horror — the Nazi concentration and extermination camps.

What they found at Buchenwald, Dachau, Bergen-Belsen, Mauthausen, and Auschwitz was not only the trace of a crime: it was the absolute silence of vanished humanity.

The soldiers, hardened by years of war, were suddenly frozen in shock.

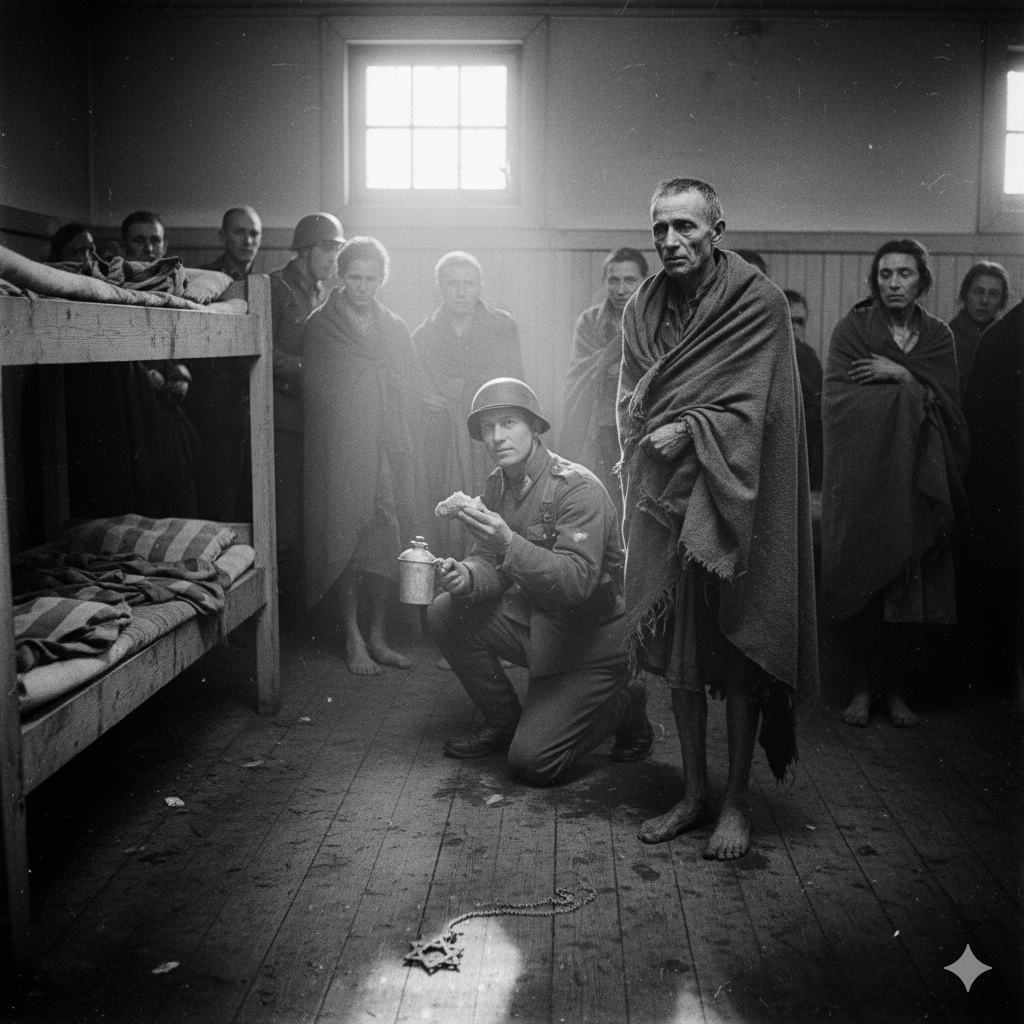

Before them stood living beings, barely recognizable: skeletal silhouettes, barefoot in the mud, dressed in striped rags, their hollow eyes still capable of a single look — that of survival.

Some reached out their hands, others hid, as if still afraid of death.

When an American soldier offered a piece of bread, several burst into tears.

That simple gesture, ordinary in a normal world, here became an act of resurrection.

The first liberation was that of Majdanek, in July 1944, when Soviet troops discovered a camp still partially in operation.

Then came Auschwitz, in January 1945 — the largest and most terrifying of all.

The Soviets found piles of shoes, hair, eyeglasses, human teeth.

Wagons filled with objects torn from interrupted lives.

That day, humanity realized that barbarism could be planned, counted, organized with method.

In April 1945, American forces reached Buchenwald and Dachau.

Reports describe the soldiers’ silence: men accustomed to war, but unprepared to discover a war waged against the human soul.

Warehouses full of ashes, ovens still warm, mountains of corpses.

And in the midst of it all, survivors too weak to understand that they were free.

An officer wrote in his notebook: “We thought we had seen everything. We had seen nothing yet.”

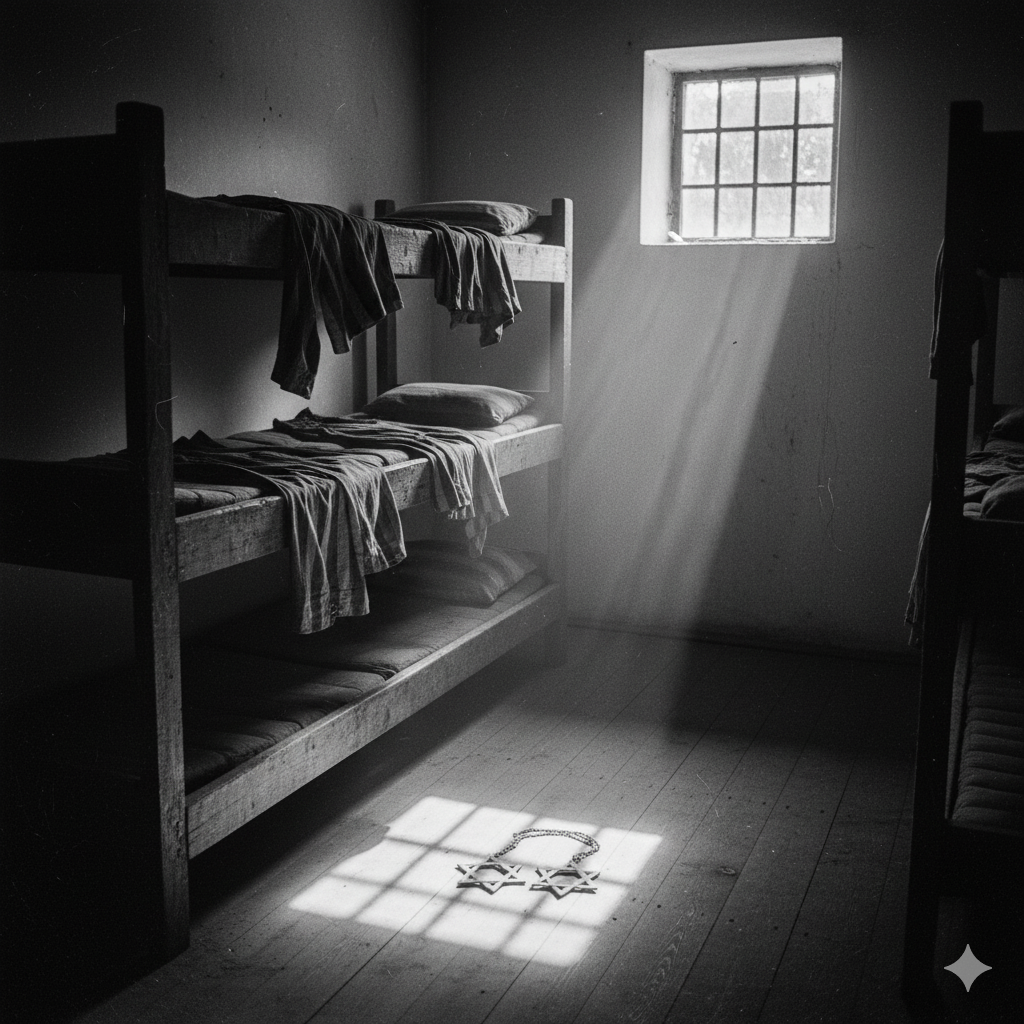

For the survivors, freedom came like a distant dream, almost unbearable.

Some collapsed as they walked toward the exit; others refused to leave the barracks, too broken to believe the nightmare had ended.

But those who managed to pass through the iron gate — often marked with cynical slogans such as “Arbeit macht frei” — took that step as an act of rebirth.

One man raised his eyes to the sky and whispered: “At last, the silence is human.”

Reconstruction was slow, painful, marked by hunger, disease, and above all, loss.

Entire families had disappeared, names erased, languages reduced to murmurs.

Yet in the heart of this void, a few found the strength to testify, to speak, to make live again those whom others had tried to erase.

Through them, memory took over where life had been extinguished.

The photographs taken during the liberation have become universal symbols.

They show not only the misery of the survivors, but also the first spark of humanity returning to a devastated world.

They remind us that a single look, a gesture of sharing, a word like “liberty” can outweigh even the deepest hatred.

Even today, these images cross the decades.

They compel us to look, to understand, to pass on.

For to forget would be to open the door to the return of evil.

To remember is to keep alive the fragile light that once nearly went out.

The day the Allied soldiers opened the gates of the camps, it was not only the end of a war.

It was the return of humanity itself — fragile, trembling, but standing tall.