When World War II ended in May 1945, Berlin lay in ruins. More than 400,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed; entire streets consisted only of rubble and burnt-out facades. The city resembled a featureless landscape, crisscrossed by craters, ruins, and makeshift paths. What today shines as a modern capital city with glass facades, wide boulevards, green spaces, and cultural centers began in near-hopeless destruction. Yet it was precisely from this state that Berlin developed into a city that constantly reinvents itself.

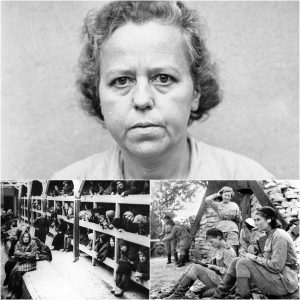

In the first postwar months, life was characterized by survival, organization, and reconstruction. Thousands of so-called “rubble women”—women who had often lost their families or whose husbands had been killed or were missing in action—formed the backbone of the early reconstruction efforts. With their bare hands, shovels, and simple tools, they cleared stone by stone, sorted usable materials, and laid the foundations for new houses. This work was not only physically demanding but also symbolic: the city was beginning to reclaim itself.

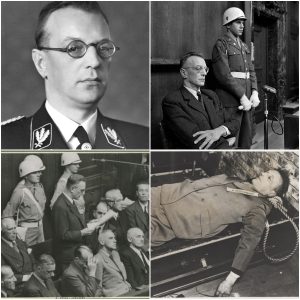

The political situation was also crucial during these years. Berlin was divided into four sectors – American, British, French, and Soviet. This division soon developed into the separation between East and West Berlin, which shaped the city for decades. Nevertheless, both sides built, albeit with differing ideological and aesthetic visions.

In the east, the focus was on large housing estates and wide boulevards, such as today’s Karl-Marx-Allee. These buildings were intended not only to provide living space but also to convey an image of unity and social organization. In the west, on the other hand, modern residential areas, commercial districts, and cultural centers were developed, drawing more heavily on international architectural styles. Both sides shared a common goal: to make Berlin livable again.

Despite progress, the city remained marked by uncertainty for decades. The construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961 cemented the division. Families were separated, routes were cut off, and public spaces lost their purpose. Yet even under these circumstances, Berlin continued to develop culturally. In West Berlin, a vibrant arts and music scene emerged, driven by young people, students, and creatives. In East Berlin, theaters, literary circles, and spaces for intellectual exchange flourished—often quietly, sometimes within the framework of state programs, sometimes in their shadow.

Discover more

Berlin Travel Blog

Tickets for memorial sites

Artworks by Berlin artists

Berlin quiz games

Berlin Nightlife Guide

Berliner Restaurants

Berlin History Books

Berlin Tourist Information

Metropolis Berlin History

Berlin Calendar

When the Wall fell in 1989, a new phase began. Once again, Berlin was a city in transition. Many buildings stood empty, vast spaces awaited new ideas, and people flocked to the streets. This feeling of openness, of new beginnings, and of collaborative creation became a core element of modern urban identity. The 1990s brought experimentation: clubs in old factories, studios in abandoned courtyards, makeshift bars in ruins that suddenly became cultural hubs.