This article discusses graphic accounts of torture, sexual violence, medical experiments, and mass murder committed during the Holocaust. The content is deeply disturbing and may trigger trauma. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

In the shadowed annals of Nazi atrocities, few figures embody the raw, personal sadism of the Holocaust as viscerally as Fritz Suhren. As the iron-fisted commandant of Ravensbrück—the Reich’s largest concentration camp for women—he turned a lakeside prison in northern Germany into a chamber of horrors where over 130,000 souls, mostly women and children, were funneled through hellish gates. Between 30,000 and 50,000 perished there from starvation, overwork, beatings, gas chambers, and grotesque medical experiments. Suhren, a mid-level SS bureaucrat who rose through the ranks on a tide of brutality, didn’t just oversee this machine of death; he reveled in it, wielding his whip and fists as instruments of intimate terror. Yet, in a final act of cowardice, his death—whether by his own hand or the swift justice of his captors—robbed survivors and the world of a complete reckoning, leaving his most depraved confessions unspoken.

Born on June 10, 1908, in a modest German farming family, Fritz Suhren’s path to monstrosity was paved with ideological fervor. He joined the Nazi Party in 1928 at age 20, enlisting in the Sturmabteilung (SA) stormtroopers before transferring to the elite SS in 1931. By 1934, he was a full-time SS man, his career a ladder of escalating cruelty. Stationed at Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1941, Suhren quickly proved his mettle as deputy commandant. There, he orchestrated one of the camp’s most infamous executions: ordering prisoner Harry Naujok, a German communist, to hang fellow inmate Johann Brenner on a gallows rigged with a winch. The device slowly hoisted the victim, prolonging his agony for 15 excruciating minutes while Suhren forced a young female inmate to stand beside the dying man, watching in forced silence. It was a prelude to the horrors he would unleash at Ravensbrück

![THE ARREST OF FRITZ SUHREN [Allocated Title] | Imperial War Museums](https://www.iwm.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-04/c_whitehead_2.jpg)

Appointed commandant of Ravensbrück in August 1942—succeeding Max Koegel, another sadist who later took his own life—Suhren inherited a camp designed exclusively for women: political dissidents, resistance fighters, Jews, Roma, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and “asocials” like lesbians and prostitutes deemed unfit for the Aryan ideal. Nestled in the Mecklenburg woods near Fürstenberg, 56 miles north of Berlin, Ravensbrück’s idyllic setting belied its savagery. Under Suhren’s rule, the camp swelled from 7,000 to over 40,000 inmates at its peak, with satellite subcamps feeding slave labor to armaments factories. His mantra was simple: extermination through exhaustion. Prisoners received rations barely sufficient for survival—rotting bread, watery soup laced with sawdust—while forced into 12-hour shifts breaking stones, sewing uniforms, or digging trenches in subzero temperatures, clad only in threadbare rags.

But Suhren’s reign was no detached administration; it was a theater of personal vendettas. Eyewitness accounts from survivors, documented in postwar trials and memoirs like Odette Sansom’s Parachute to Peril, paint Suhren as a hands-on tormentor. Tall, broad-shouldered, and sporting a perpetual sneer, he patrolled the barbed-wire enclosures with a horsewhip coiled at his belt, selecting women at whim for “disciplinary measures.” He was notorious for flogging prisoners to death in the camp’s courtyard, his blows landing with rhythmic precision on bare backs until flesh split and bones cracked. “He beat them until they stopped moving,” recalled one Polish survivor, Maria Kusmierczuk, in testimony at the 1947 Hamburg Ravensbrück Trials. Suhren reveled in the spectacle, often pausing to light a cigarette amid the screams, ensuring the assembled inmates witnessed the “lesson.” Personal punishments were his specialty: for minor infractions like a whispered conversation or a stumbled step in formation, he dragged women to his office for solitary “interrogations.” There, isolated from the block’s eyes, he unleashed unbridled fury—pummeling faces until jaws shattered, kicking ribs until lungs collapsed, or worse, subjecting them to sexual humiliations that left indelible scars on the psyche.

These acts weren’t mere outbursts; they were Suhren’s signature. Unlike the clinical detachment of Auschwitz’s doctors, Suhren’s violence was tactile, eroticized in its intimacy. He oversaw the “Joy Division”—a euphemism for a brothel where “privileged” prisoners were coerced into sex with male guards and favored inmates, many dying from venereal diseases or suicide. He personally vetted selections for this degradation, his gaze lingering as women were paraded before him. And when Heinrich Himmler’s chief surgeon, Karl Gebhardt, arrived in 1942 demanding subjects for “medical research,” Suhren initially balked—most Ravensbrück women were “politicals,” not Jews, he protested. But orders were orders. Apologizing profusely in a letter to Gebhardt, Suhren complied, supplying hundreds for experiments that sterilized with radium injections, infected limbs with gangrene bacteria, shattered bones only to transplant fragments without anesthesia, and tested sulfonamide drugs on deliberately wounded flesh. Suhren even toured the “infirmary,” chuckling at the writhing forms strapped to tables.

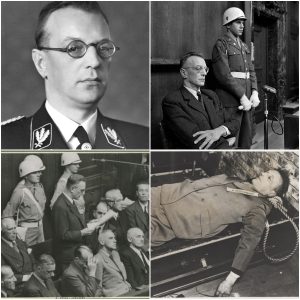

As the Red Army closed in April 1945, Suhren’s facade cracked. With liberation looming, he orchestrated death marches that claimed thousands more lives, abandoning the weak to freeze in ditches. In a bizarre bid for mercy, he bundled British SOE agent Odette Sansom—whom he delusionally believed was Winston Churchill’s niece—into his Mercedes, pistol in hand, and drove to American lines. “Take this,” he reportedly said, handing her his Walther PPK as a token of surrender, hoping her “connections” would shield him. Sansom, who had endured torture without breaking, pocketed the weapon as a trophy, now displayed at London’s Imperial War Museum. Arrested by British forces, Suhren seemed poised for judgment.

But the monster slipped the noose once more. In 1946, while awaiting transfer for the Hamburg Trials—where 16 other Ravensbrück staff were convicted—Suhren escaped British custody alongside labor chief Hans Pflaum, vanishing into Bavaria’s black market. For three years, he evaded the net, his absence a gaping wound in the historical record. The Hamburg proceedings cataloged Ravensbrück’s systemic horrors but could only speculate on Suhren’s direct role, piecing together survivor fragments without his cross-examination. “His flight silenced the full extent of his personal crimes,” noted prosecutor Telford Taylor in postwar reflections. Recaptured in 1949 by U.S. troops, Suhren was extradited to a French military court in Rastatt, where a jury of Allied survivors—French, Dutch, Luxembourgish—sat in judgment from February to May 1950.

The trial was a torrent of anguish. Dozens testified to Suhren’s whippings, his office rapes, the experiments he greenlit. Interrogation protocols reveal Suhren’s defiance: he admitted to “maintaining order” but denied specifics, blaming superiors like Himmler. “I followed orders,” he shrugged, echoing the Nuremberg defense. On May 15, 1950, the verdict rang out: guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Death by firing squad. Suhren’s end came swiftly on June 12, 1950—just two days after his 42nd birthday—in a pine-shrouded field near Rastatt. Eyewitnesses described him facing the muzzles without remorse, his last words a muttered curse.

In death, Suhren achieved a perverse victory. His escape and abbreviated testimony cheated the world of deeper insight into the psychology of a man who murdered not for ideology alone, but for the thrill of broken bodies at his feet. Survivors like Sansom, who lived until 1995, carried the weight of unspoken horrors, their justice partial. Ravensbrück’s ghosts whisper of what might have been revealed had Suhren lived to face every lash he dealt. His story isn’t one of redemption or even poetic irony—it’s a reminder that monsters like him die, but the silence they impose lingers, a final whip-crack in the dark.

Today, the Ravensbrück Memorial Site stands as testament: a museum amid the ruins, where wildflowers bloom over mass graves. It honors the “Rabenmütter”—the raven mothers—who resisted, survived, and testified. Suhren’s crimes, though partially shrouded, fuel the vow: never again. But as we reckon with resurgent hatreds, his unchallenged depravities urge vigilance. The monster may be silenced, but memory demands we shout.