How Two Criminal Trials Marked The End Of A Centuries-Old Practice**

When discussing France’s long and complex legal history, the use of the guillotine often evokes images from the 18th and 19th centuries. It may be surprising to many that this method of capital punishment remained in use until the late 1970s. Two cases in particular — those of Eugen Weidmann in 1939 and Hamida Djandoubi in 1977 — played important roles in shaping public opinion and the eventual end of the practice.

This article explores these events from a historical and educational perspective, focusing on how changing social values and legal reforms gradually brought an era to a close.

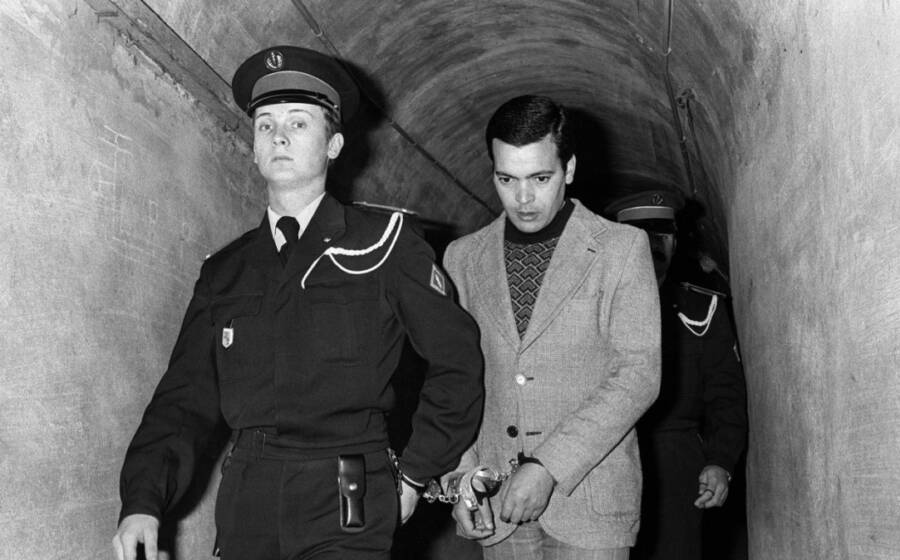

The Case of Hamida Djandoubi (1977)

Hamida Djandoubi, a Tunisian immigrant living in France, was tried and sentenced in 1977 for a serious criminal case involving the death of a young woman. After exhausting the appeals process, his sentence was carried out privately at Baumettes Prison in Marseille on September 10, 1977.

What makes this event historically significant is that it marked the final use of the guillotine in France. By the late 20th century, both public sentiment and the political climate were strongly shifting away from capital punishment. Djandoubi’s case occurred during a period of intense national debate, and within four years, in 1981, France formally abolished the death penalty altogether.

His execution symbolized the end of a long chapter in French legal history and became an important point of reference in discussions about justice, human rights, and penal reform.

The Case of Eugen Weidmann (1939)

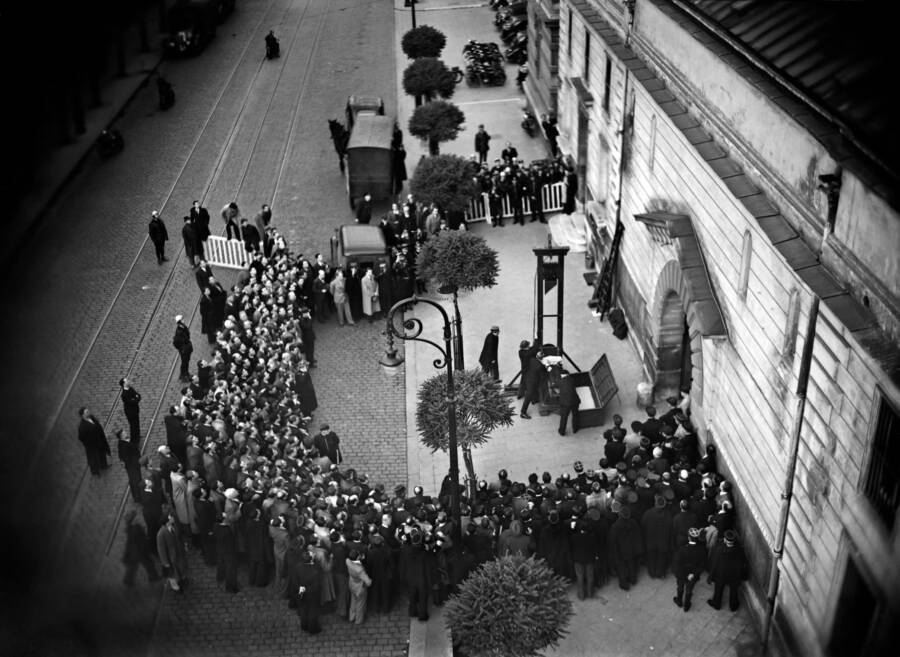

Eugen Weidmann was tried in the late 1930s for a series of violent crimes committed in France. After his conviction, an execution was carried out on June 17, 1939, outside the prison in Versailles.

This event is remembered not for its legal aspects alone, but for its public nature. Large crowds gathered, and the highly emotional atmosphere surrounding the event prompted immediate government concern. The French president at the time, Albert Lebrun, issued a decision that all future executions would be conducted away from public view.

Thus, Weidmann became the last person to face a public execution in France. His case significantly accelerated discussions about legal dignity, ethics, and the role of public spectacle in criminal justice.

Changing Public Opinion and the End of Capital Punishment

Following Weidmann’s case, France transitioned to private, closed-door procedures. Over the next decades, legal scholars, human-rights advocates, and political leaders increasingly questioned the place of capital punishment in a modern society.

By the 1970s, the debate had gained momentum:

-

Public support for abolition continued to grow.

-

Human rights movements emphasized rehabilitation over retribution.

-

European partners encouraged a shift toward non-violent penal systems.

The final turning point came in 1981 when Justice Minister Robert Badinter championed the complete abolition of the death penalty — a reform passed by President François Mitterrand’s government that same year.

Historical Legacy

Today, the cases of Eugen Weidmann and Hamida Djandoubi are studied not for their sensational elements, but for their legal and historical importance:

-

They highlight how public perception influences criminal justice.

-

They show the evolution of ethical standards in modern Europe.

-

They mark the transition away from capital punishment in France.

Museums, academic studies, and legal institutions continue to reference these cases as part of the broader discussion on justice, societal values, and the protection of human dignity.

Conclusion

The stories of France’s last guillotine cases represent more than isolated criminal trials. They symbolize the transformation of a nation’s approach to justice and human rights. Through examining how society responded to these events, we gain insight into how legal systems evolve — and how cultural values shape the laws that govern us.