Content Warning: This article discusses historical persecution, including imprisonment and forced medical procedures, which may be distressing. It aims to educate on human rights violations and their historical context.

During the Nazi regime (1933–1945), gay men faced severe persecution under Paragraph 175 of the German criminal code, which criminalized male homosexuality since 1871. Despite a growing gay community in the Weimar Republic, the Nazis intensified enforcement, targeting gay men as threats to their ideology of “Aryan” purity and traditional family structures. Approximately 100,000 men were arrested, with over 53,000 convictions, many sent to concentration camps where they endured extreme abuse. This analysis, based on sources like the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and survivor accounts, examines the Nazi campaign against gay men, its mechanisms, and its impact, fostering discussion on human rights and the dangers of discrimination.

Pre-Nazi Context and Weimar Liberalization

In the mid-to-late 19th century, Germany saw the emergence of nascent gay communities, particularly in urban areas. The Weimar Republic (1918–1933) offered relative openness, with advocates like Magnus Hirschfeld campaigning for the repeal of Paragraph 175, which banned male homosexual acts. Gay bars and cultural spaces flourished, though legal risks persisted.

The Nazi Party, rising in the 1920s, opposed decriminalization, viewing homosexuality as a deviation undermining their racial and familial ideals. Even so, figures like Ernst Röhm, SA leader and openly “same-sex oriented,” existed within the party, creating ideological contradictions.

Nazi Seizure of Power and Initial Crackdowns

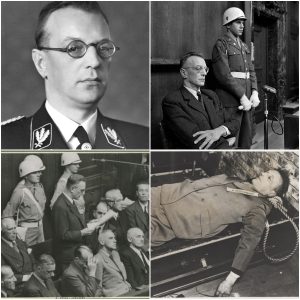

On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler became Chancellor, and the Nazis began dismantling Weimar’s gay networks. By late 1933, under Heinrich Himmler’s leadership, Reinhard Heydrich, deputy of the Bavarian Political Police, ordered “pink lists” to identify homosexuals in major cities. These lists facilitated raids on gay bars and mass arrests in 1934, targeting men uninvolved in politics.

The Gestapo, as the political police, detained suspects without trial. Courts introduced mandatory castration for certain offenders in 1933, though initially requiring consent. Men convicted under Paragraph 175 could secure early release by volunteering for castration, as did Friedrich-Paul von Groszheim, arrested in 1934.

Escalation of Persecution (1934–1936)

Three pivotal events intensified the campaign:

Röhm Purge (June–July 1934): The murder of Ernst Röhm and SA leaders during the Night of the Long Knives was partly justified by Nazi propaganda citing Röhm’s homosexuality, framing it as moral corruption.

Paragraph 175 Revision (June 1935): The law was expanded to criminalize a broader range of homosexual acts, lowering the evidence threshold and increasing penalties.

Reich Central Office (1936): Himmler established the Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion, centralizing efforts to suppress both as threats to population growth.

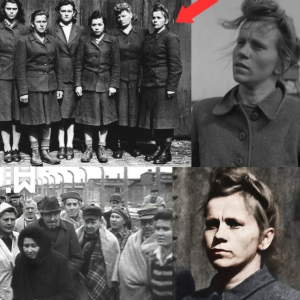

By 1935–1936, police raids on gay meeting places intensified, driven by denunciations from neighbors, colleagues, or family. Scholar Robert Moeller notes the regime’s use of fear to isolate gay men.

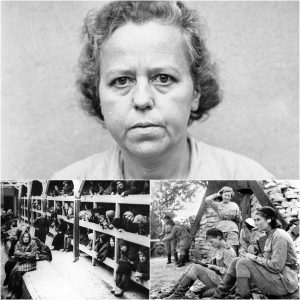

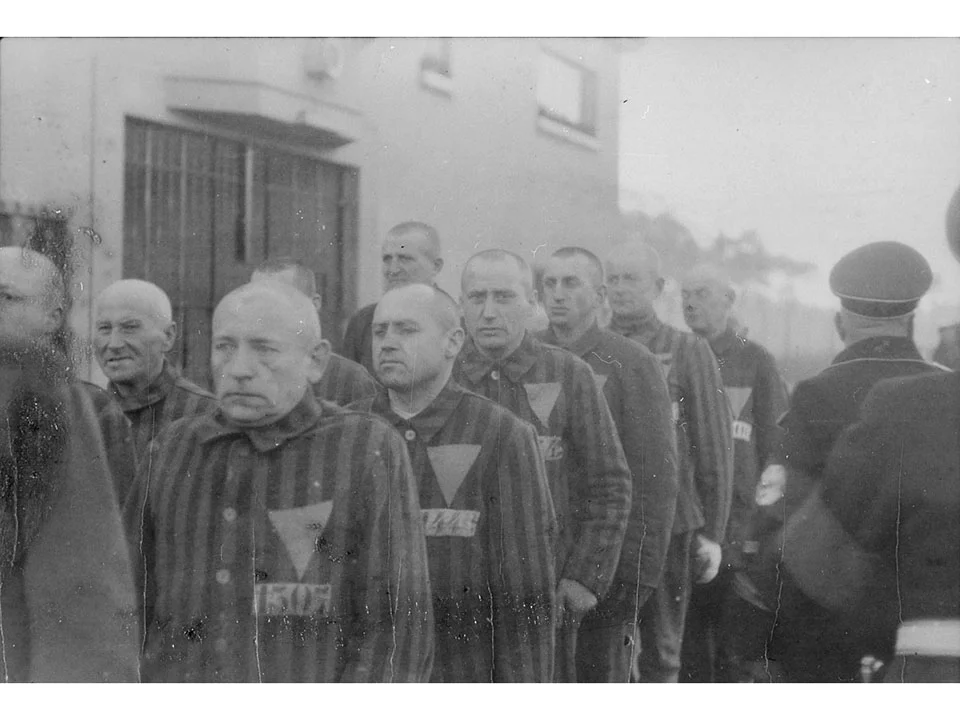

Concentration Camps and Pink Triangles

Gay men convicted under Paragraph 175 were sent to camps like Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald, marked by pink triangles to identify them. Approximately 5,000–15,000 were imprisoned, facing brutal treatment. Survivor accounts, such as Josef Kohout’s, arrested in March 1939 after his Christmas card to a lover was intercepted, describe sadistic abuse by SS guards, including beatings and murders during “games.”

From November 1942, camp commandants could order forced castrations for pink triangle prisoners, often without consent. Kohout, aged 24 at arrest, endured such conditions. Scholars estimate 100,000 arrests under Paragraph 175, with over 53,000 convictions, reflecting the campaign’s scale.

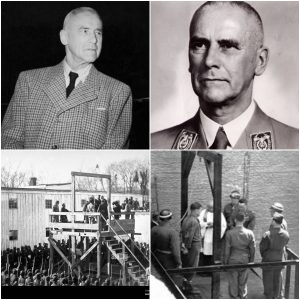

Post-War Legacy and Challenges

After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, many gay survivors faced continued stigma. Paragraph 175 remained in effect in West Germany until 1969, and convictions were not overturned until the 1990s. Victims like Kohout received no reparations until late reforms, with formal apologies issued by Germany in 2002.

The persecution decimated gay communities, erasing Weimar’s cultural gains. Memorials, such as Berlin’s Monument to Homosexual Victims, and survivor testimonies preserve their stories.

The Nazi persecution of gay men under Paragraph 175 was a systematic effort to erase a marginalized group, costing thousands of lives and livelihoods. For history enthusiasts, this history underscores the fragility of human rights and the dangers of discriminatory ideologies. By studying sources like the USHMM, we honor survivors like Josef Kohout and advocate for inclusivity, encouraging dialogue to prevent such atrocities.