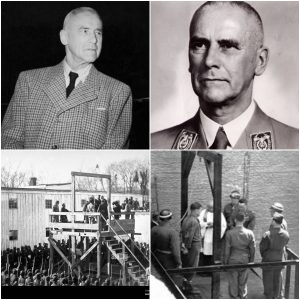

In the dim, echoing gymnasium of Nuremberg Prison, as the clock ticked past 2:40 a.m. on October 16, 1946, a limping figure ascended the wooden scaffold—the last of ten condemned Nazi architects to face the noose. Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the bespectacled bureaucrat whose clubfoot mirrored the twisted path of his ideology, mounted the thirteen steps with eerie composure. His voice, low and intense, carried a final plea for peace amid the ruins of the war he had helped unleash: “I hope that this execution is the last act of the tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from this world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between peoples.” But as the trapdoor yawned beneath him, his calm shattered in a guttural roar: “I believe in Germany!”—a defiant scream that echoed through the chamber like a ghost refusing to die. At precisely 2:45 a.m., Seyss-Inquart dropped through the gallows, his body jerking in the final spasm of a regime that had devoured nations. This was no mere end; it was the chilling coda to a life built on extermination, a man who, much like his counterpart Hans Frank in occupied Poland, turned sovereign soil into slaughterhouses of the soul.

Born on July 22, 1892, in the Bohemian town of Stannern (now Hranice na Moravě in the Czech Republic), Arthur Seyss-Inquart emerged from the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a decorated World War I veteran, wounded in the trenches and later a lawyer in Vienna. By the 1930s, his fervent pan-Germanism drew him into the shadows of the Nazi orbit. He championed the “legal” faction of Austrian Nazis, advocating Anschluss—the violent union with Germany—while serving in Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg’s government as Minister of Interior and Security. When Hitler demanded his installation as chancellor on March 11, 1938, Seyss-Inquart complied without hesitation, holding the post for just two days before German troops stormed across the border. He welcomed the invasion with open arms, becoming Reichsstatthalter (Governor) of the newly minted Ostmark province, purging Jews from professions and laying the groundwork for the Holocaust in his homeland.

Seyss-Inquart’s ascent continued unchecked. In May 1939, Hitler elevated him to Reichsminister without portfolio, and by October, he served as Deputy Governor-General under Hans Frank in the brutal General Government of occupied Poland—a territory Frank managed with genocidal zeal, overseeing ghettos, mass shootings, and the deportation of millions to death camps like Auschwitz and Treblinka. Seyss-Inquart, ever the efficient administrator, mirrored Frank’s territorial tyranny: suppressing resistance, enforcing Aryanization, and ensuring the machinery of murder hummed smoothly. Their roles were eerily parallel—bureaucrats of barbarism, transforming conquered lands into laboratories of death, where human lives were reduced to quotas on ledgers.

But it was in the Netherlands where Seyss-Inquart’s legacy of annihilation crystallized into infamy. Appointed Reichskommissar on May 29, 1940, mere weeks after the Blitzkrieg blitz, he ruled the five-year occupation with a velvet glove over an iron fist, answering directly to Hitler. From his headquarters in The Hague, he orchestrated a reign of calculated cruelty. He banned opposition parties, politicized culture through the Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer, and unleashed the paramilitary Nederlandse Landwacht to terrorize dissenters. Strikes in Amsterdam, Arnhem, and Hilversum in 1943 met swift reprisal: summary courts-martial, collective fines of 18 million guilders, and over 800 executions—some accounts tally more than 1,500—of hostages, resistance fighters, and innocents caught in the crossfire. The Putten raid of 1944, a vengeance for an attack on SS leader Hanns Albin Rauter, saw 117 villagers shot and thousands deported, their village razed to rubble.

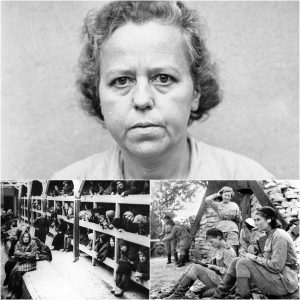

Yet Seyss-Inquart’s deadliest decree was reserved for the Jews. An unyielding anti-Semite, he wasted no time: Within months, he purged them from civil service, press, and industry. By 1941, 140,000 Dutch Jews were registered, herded into Amsterdam’s ghetto, and funneled through Westerbork transit camp—a former refugee haven twisted into a conveyor belt to hell. The February 1941 razzia deported 600 to Buchenwald and Mauthausen; by war’s end, trains rattled ceaselessly to Auschwitz, claiming 107,000 lives. Only 30,000 Dutch Jews survived—a 75% annihilation rate unmatched in Western Europe. As Allies closed in during September 1944, he diverted the remnants to Theresienstadt, a facade of mercy masking further slaughter.

Forced labor was his other scourge. Under his watch, 530,000 Dutch civilians were conscripted, with 250,000 shipped to German factories as slave workers, their bodies broken in the service of the Reich. Camps like Herzogenbusch (Vught), Amersfoort, and the infamous Erika at Ommen became extensions of his terror state. The 1944–1945 “Hunger Winter” starved 20,000 more, as his policies choked food supplies amid scorched-earth retreats—though, in a rare flicker of restraint, he negotiated Allied airlifts in April 1945. In total, Seyss-Inquart’s ledger of death tallied hundreds of thousands: Jews gassed, laborers crushed, hostages slain, and civilians starved. He was the architect of Dutch annihilation, a quiet engineer whose edicts echoed Frank’s Polish playbook but on the wind-swept dunes of the Low Countries.

As the Third Reich crumbled, Seyss-Inquart’s star dimmed. In Hitler’s April 1945 testament, he was named Foreign Minister, a hollow honor in the bunker’s delirium. Captured by British forces in Hamburg on May 5, 1945—ironically by a German Jewish Kindertransport survivor—he faced the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Defended by Gustav Steinbauer, he aced an IQ test with a score of 141, second only to Hermann Göring among the defendants, a testament to the intellect that fueled his evil. Acquitted of conspiracy, he was convicted on all other counts: crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. The judges excoriated his “reign of terror” in the Netherlands—the deportations, the executions, the unyielding grip on a nation’s throat.

In his final trial statement, Seyss-Inquart feigned ignorance of atrocities, claiming moral qualms over Jewish deportations while equating them to postwar Allied expulsions of Germans. “My conscience is clear,” he insisted, asserting he had “improved” Dutch conditions—a grotesque revisionism from the man who buried a people. Upon sentencing, he shrugged fatalistically: “Death by hanging… well, in view of the whole situation, I never expected anything different. It’s all right.” He returned to the Catholic faith, seeking absolution from chaplain Father Bruno Spitzl, but the blood on his hands could not be washed away.

The execution chamber on that autumn night was a theater of retribution. One by one, the condemned—Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Rosenberg, Frick, Streicher, Sauckel, Jodl, Frank, and Ribbentrop—had dropped, their bodies swaying like pendulums of justice. Göring, cheated of the noose by suicide, lay unceremoniously nearby. Seyss-Inquart, the finale, limped forward, his unsteadiness belying the steel in his convictions. Guards steadied him as he uttered his scripted hope for peace, a hollow echo in a hall stained by the screams of millions. Then, as the lever was pulled, came the scream—”I believe in Germany!”—a last, throaty affirmation of the fatherland that had birthed his monstrosity. His neck snapped at 2:45 a.m., the trapdoor’s thud marking the close of Nuremberg’s grim pageant.

Seyss-Inquart’s body was cremated at Munich’s Ostfriedhof, his ashes scattered anonymously in the Isar River, denying even a grave to the unrepentant. Beyond the verdict—not in The Hague, but in the Bavarian courtroom that redefined justice—his end exposes the banality of bureaucratic evil. He was no ranting fanatic like Streicher, no ideologue like Rosenberg; he was the calm calculator, the manager of mayhem, whose spreadsheets sentenced souls. In his defiant yelp from the gallows, we hear not just a man’s final gasp, but the Reich’s undying delusion. And in the silence that followed, a world exhaled, vowing never again—though history, ever watchful, knows better.