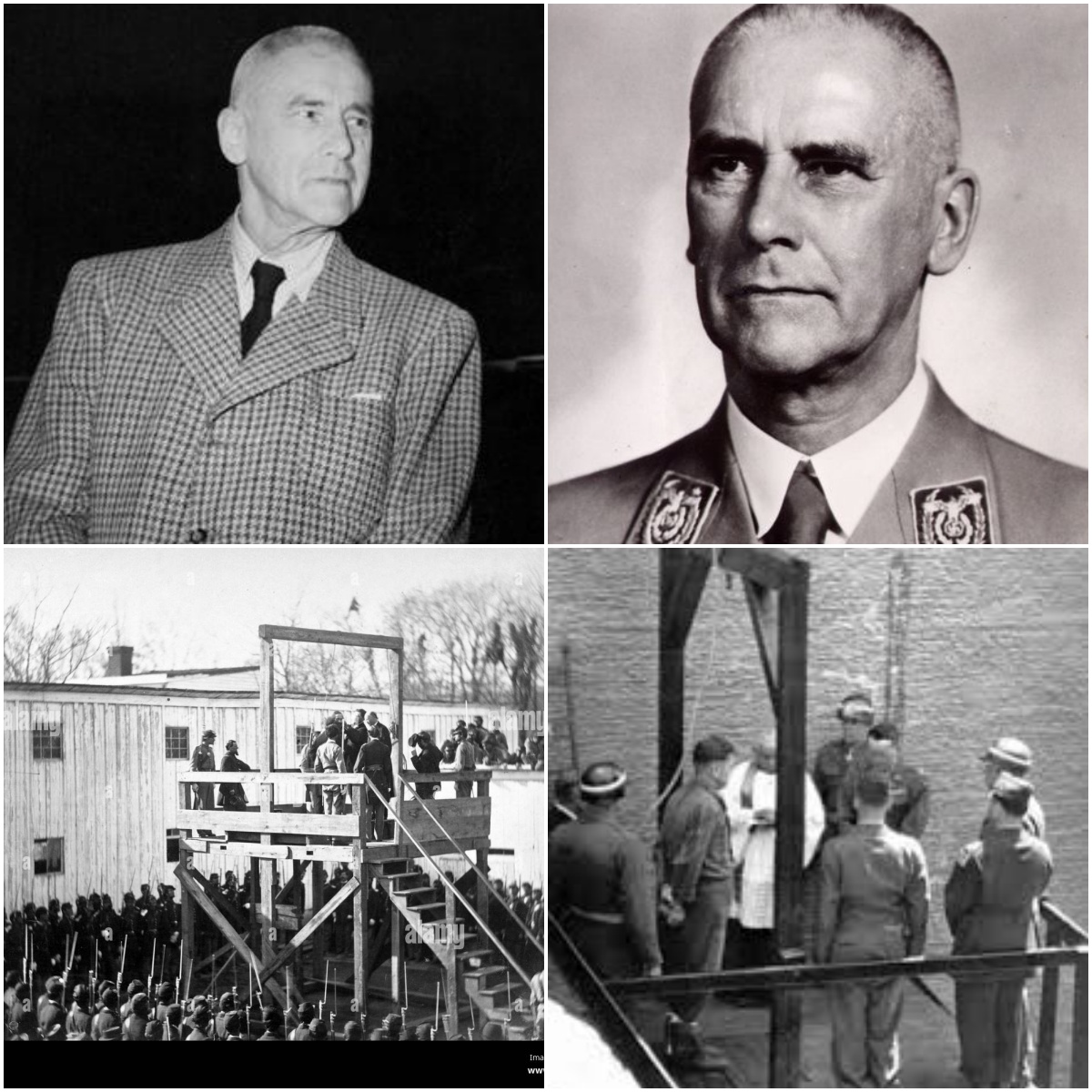

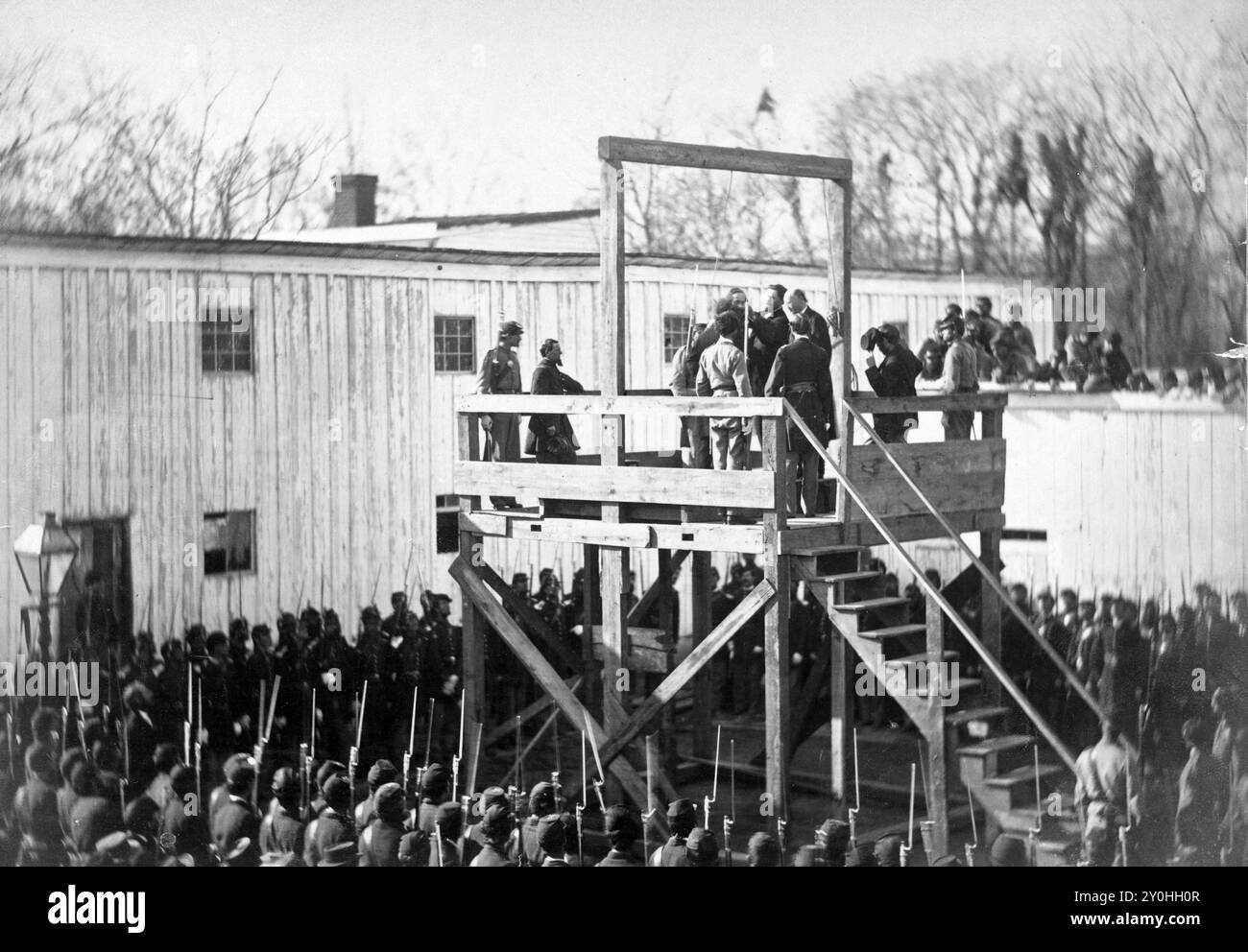

On the early morning of October 16, 1946, in the dimly lit execution chamber at Nuremberg Prison, Germany, Ernst Kaltenbrunner—one of the most notorious leaders of the Nazi regime—stepped onto the gallows with an eerily calm demeanor. Standing over 1.9 meters tall, with a gaunt face scarred from student dueling bouts, and a low, resonant voice, he offered no resistance. When invited to speak his final words, Kaltenbrunner whispered in German: “I have loved the German people and my country with a warm heart. I have fulfilled my duty according to the laws of my people, and I regret that my people this time were led by those who were not soldiers, and that crimes were committed which I did not know about.” As the black hood was pulled over his head, he murmured: “Germany, good luck.” Mere seconds later, the trapdoor sprang open, and his towering body plummeted, ending a life directly tied to the deaths of millions in the Holocaust. Those whispers, laden with deceit and evasion of responsibility, have become a symbol of the blindness of those who executed the “Final Solution”—humanity’s darkest chapter in history.

Ernst Kaltenbrunner was born on October 4, 1903, in Ried im Innkreis, Austria, into a family of lawyers steeped in extreme nationalist sentiments. He grew up near Braunau—Adolf Hitler’s birthplace—and from a young age absorbed völkisch Pan-Germanist ideology, marked by anti-Semitism and viewing political conflict as racial warfare. In his childhood, Kaltenbrunner befriended Adolf Eichmann—the future “architect” of Holocaust logistics. After graduating from the Realgymnasium in Linz in 1921, he studied chemistry at the University of Graz but switched to law in 1923. There, he joined nationalist student associations, protesting against Marxism and church influence. In 1926, he earned his doctorate in law and opened a law practice in Linz. His scar-riddled face—from fencing duels or a car accident—added to his intimidating appearance, even making Heinrich Himmler wary.

In 1929, Kaltenbrunner joined the Heimwehr—a paramilitary anti-Marxist organization—and by 1930, he officially entered the Nazi Party (membership number 300,179). In 1931, he joined the SS (number 13,039) on the recommendation of Sepp Dietrich, quickly becoming legal advisor to the SA and SS in Austria. Despite two arrests by the Austrian government under Engelbert Dollfuss for plotting a coup (1934 and 1935), Kaltenbrunner secretly built an SS intelligence network in Austria, providing information to Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich, and Heinz Jost. Himmler—viewing him as his “right-hand man” in Austria—kept him in place to strengthen the local SS, and in 1937, appointed him commander of the entire Austrian SS. His clandestine trips to Bavaria, smuggling photocopied documents on Austrian foreign policy, elevated him as a trusted figure in Nazi leadership.

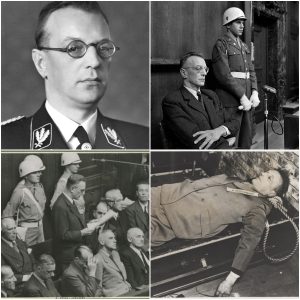

Austria’s collapse came swiftly after the Anschluss in 1938. Kaltenbrunner assisted Arthur Seyss-Inquart in annexing Austria into the Third Reich and was appointed State Secretary for Public Security from March 11 to 13, 1938. He oversaw the Nazification of Austrian society, establishing the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp—the first Nazi camp in Austria—and was promoted to SS-Gruppenführer (equivalent to lieutenant general). By 1940, he served as Vienna’s police chief and built an extensive intelligence network, catching Himmler’s eye. After Heydrich’s assassination in 1942, Himmler temporarily led the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office) before appointing Kaltenbrunner as its chief on January 30, 1943—a surprising choice by Hitler, who saw him as a “pliable newcomer” compared to candidates like Heinrich Müller or Walter Schellenberg.

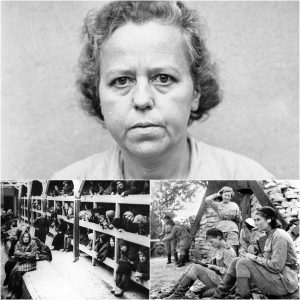

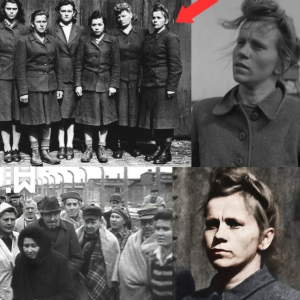

Under Kaltenbrunner, the RSHA became a colossal killing machine, unifying the Gestapo (State Secret Police), Kripo (Criminal Police), and SD (Security Service). He oversaw repression campaigns, arrests, deportations, and executions across Europe, while commanding the Einsatzgruppen—mobile killing squads responsible for over 1 million deaths, mostly Jews, in the East. A fervent anti-Semite, Kaltenbrunner was directly involved in the “Final Solution.” He attended a December 1940 meeting with Hitler, Himmler, Heydrich, and Joseph Goebbels, where it was decided to gas all Jews unfit for heavy labor. In 1943, he pushed the Justice Ministry to enforce mandatory castration for homosexuals, reviewing 6,000 military cases. During a 1943 inspection of Mauthausen, he witnessed 15 prisoners shot, hanged, and gassed in a “demonstration” of killing methods, then inspected the crematoria and quarry.

Kaltenbrunner’s role in the Holocaust peaked in 1944. At Klessheim Castle, he helped coerce Hungarian Admiral Miklós Horthy into Nazi collaboration, enabling Eichmann to deport 750,000 Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz with an Einsatzkommando. In October 1943, he instructed Herbert Kappler in Rome that exterminating Italian Jews was a “special priority for general security,” leading to the roundup and transport of 1,000 Roman Jews to Auschwitz in just four days. He signed orders accelerating genocide, liquidating Jewish areas in the Reich and occupied territories, and received regular reports on camp operations. Kaltenbrunner also expanded his influence by succeeding Heydrich as Interpol president from 1943 to 1945, using it to hunt Jews and political enemies. His relationship with Himmler blended loyalty and fear: Himmler appointed him, but Kaltenbrunner’s volatile temper reportedly intimidated even Himmler. By 1945, Himmler tasked him with commanding southern German forces.

As the war crumbled, Kaltenbrunner clung to power. After the July 20, 1944, plot to assassinate Hitler, he investigated and pushed for the execution of about 5,000 suspects. In February 1945, he ordered police to shoot “traitors” without trial. But by April 1945, he fled Berlin for the Totes Gebirge mountains near Altaussee, Austria. On May 12, he was captured by the U.S. Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps Team 80 after a witness identified him despite his alias as a doctor.

At the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg, Kaltenbrunner was charged with conspiracy to commit crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Initially absent due to a brain hemorrhage, he denied all responsibility upon appearing: claiming signatures on extermination orders were forged by aides, his role limited to intelligence, and he “knew nothing of the Final Solution before 1943,” even “opposing mistreatment of Jews” and “ending it.” These defenses drew laughter in the courtroom—witness Hans Bernd Gisevius called him “worse than the monster Heydrich.” On September 30, 1946, the tribunal acquitted him of crimes against peace but convicted him of war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentencing him to death by hanging.

On the morning of October 16, 1946, Kaltenbrunner was the seventh to enter the execution chamber. Dressed in a blue coat, he responded softly to his name. His final words—a delusional whisper of “love for Germany”—could not obscure his direct responsibility for millions of destroyed lives. His body was cremated at Munich’s Eastern Cemetery, with ashes scattered in the Isar River. Today, Kaltenbrunner remains a symbol of systematic cruelty: a lawyer once promising legal protection for SA/SS now the architect of hell. The whisper on the gallows was no confession, but an eternal reminder of the cost of extreme nationalism and silence in the face of atrocity.