EXTREMELY SENSITIVE CONTENT – 18+ ONLY

This article discusses sensitive historical events involving death and tragedy during World War II. It is intended for educational purposes only, to provide insight into the consequences of extremism and the human cost of war. It is recommended for readers aged 18 and above. The content does not promote violence, extremism, or any harmful ideologies in any form.

Opening The Coffin Of Magda Goebbels – The First Lady Of The Third Reich

In the annals of World War II history, few figures embody the dark intersection of personal loyalty and ideological fanaticism as starkly as Magda Goebbels. Often referred to as the “First Lady of the Third Reich,” she was the wife of Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler’s infamous Minister of Propaganda. Her life, marked by privilege, influence, and ultimately tragedy, culminated in one of the most harrowing episodes of the war’s final days. While her death in the Reich Chancellery bunker in Berlin is well-documented, a lesser-known chapter unfolded decades later: the exhumation of her remains 25 years after the war’s end. This event, shrouded in secrecy and carried out by Soviet authorities, serves as a poignant reminder of how the shadows of the Nazi era lingered long after the guns fell silent. Through this historical lens, we explore not just the facts, but the broader lessons on the perils of blind devotion to destructive regimes.

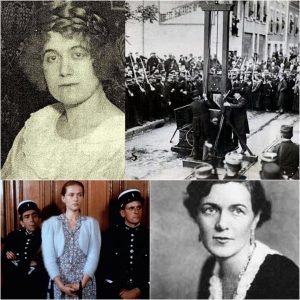

Magda Goebbels, born Johanna Maria Magdalena Ritschel on November 11, 1901, in Berlin, rose from modest beginnings to become a symbol of Nazi elegance and propaganda. Her early life was unconventional; raised by her mother after her parents’ divorce, she experienced a blend of Catholic and Jewish influences through her stepfather, Richard Friedländer, a Jewish businessman. This background, ironically, contrasted sharply with her later embrace of Nazi ideology. In 1921, she married Günther Quandt, a wealthy industrialist, and bore him a son, Harald. The marriage ended in divorce in 1929, but it provided her with social standing and connections that would propel her into the Nazi elite.

Her fateful meeting with Joseph Goebbels came in 1930, when she joined the Nazi Party and began working in its propaganda offices. Captivated by Goebbels’ charisma and shared ideological fervor, they married in 1931, with Hitler himself serving as a witness. The couple became the epitome of the “ideal Aryan family,” producing six children—Helga, Hildegard, Helmut, Holdine, Hedwig, and Heidrun—whose images were frequently used in Nazi media to promote racial purity and family values. Magda’s role extended beyond homemaking; she hosted lavish events, supported women’s organizations within the party, and even influenced cultural policies. Yet, beneath this polished facade lay a woman deeply entangled in the regime’s atrocities, complicit through her unwavering support for her husband and Hitler.

As the Allies closed in on Berlin in April 1945, the Goebbels family sought refuge in the Führerbunker, the underground complex beneath the Reich Chancellery. With the Soviet Red Army encircling the city, the end of the Third Reich was imminent. Hitler and his new wife, Eva Braun, died by suicide on April 30. Joseph Goebbels briefly assumed the role of Reich Chancellor but, realizing defeat was inevitable, chose to end his life the following day. Magda, driven by a distorted sense of loyalty and fear of a world without Nazism, made a devastating decision regarding her family. Historical accounts, based on survivor testimonies and forensic evidence, indicate that she administered poison to her six children, aged 4 to 12, in a misguided belief that death was preferable to capture or a life under Allied rule. She and Joseph then took their own lives, likely through cyanide and gunfire.

The immediate aftermath was chaotic. Loyal SS personnel attempted to cremate the bodies in the Reich Chancellery Garden to prevent desecration, but fuel shortages left the remains only partially burned. Soviet troops, upon capturing Berlin in early May 1945, discovered the charred corpses. Autopsies conducted by Soviet pathologists confirmed the identities through dental records and other markers. The bodies of Joseph, Magda, and their children were initially buried in shallow graves near the bunker, but concerns over potential Nazi sympathizers turning the site into a shrine prompted repeated relocations.

Over the ensuing years, the remains were exhumed multiple times under Soviet control. They were first moved to Finow, then to Rathenow, and eventually to Magdeburg in East Germany, where they were interred in unmarked graves at a military facility. This secrecy was part of a broader Soviet strategy to erase any physical traces of Nazi leaders, denying them posthumous veneration. For 25 years, from 1945 to 1970, Magda Goebbels’ body lay in relative obscurity, a forgotten relic of a fallen empire.

The pivotal exhumation occurred in 1970, when the Magdeburg site was transferred from Soviet to East German control. Fearing that the graves could become focal points for neo-Nazi activities, KGB operatives—under orders from Yuri Andropov, then KGB chairman—oversaw the final disinterment. Accounts from declassified documents and eyewitness reports describe a somber operation: the coffins were opened, and the remains, preserved in varying states due to the initial charring and subsequent burials, were thoroughly cremated. The ashes were then scattered into the Ehle River near Biederitz, Saxony-Anhalt, ensuring no physical remnants survived. This act, carried out by a Soviet lieutenant named Gumenjuk, marked the definitive end to any potential for memorialization.

This exhumation was not merely logistical; it symbolized the Cold War-era determination to prevent the resurrection of fascist ideologies. While details remained classified for decades, they emerged through historical research and memoirs, offering scholars insights into postmortem handling of war criminals. It underscores the ethical dilemmas of dealing with the dead in the context of genocide and totalitarianism—questions that resonate in modern discussions about historical memory and justice.

The story of Magda Goebbels’ exhumation, 25 years after World War II’s conclusion, closes a grim chapter in history. From her rise as a propaganda icon to her tragic end and the erasure of her physical legacy, it illustrates the profound human costs of fanaticism. This narrative serves as an educational tool, reminding us of the importance of vigilance against extremism and the value of learning from the past to build a more just future. By examining such events responsibly, we honor the victims of that era and commit to preventing its horrors from recurring.

Confirmed by official & credible sources

Declassified KGB report from 1970 (declassified in 2007) – “Operation Archive” file, currently held in the FSB Archive, Moscow (partially published in the book below).

Chelmsford, Krisztián, & Ritter, Markus: *Die Vernichtung der Gebeine der Familie Goebbels – Die KGB-Akte 1970* (Ch. Links Verlag, Berlin 2019).

Le Tissier, Tony: The Battle of Berlin 1945 and the appendix “Disposal of the Goebbels Family Remains” (Appendix VI), based on the direct testimony of Colonel Vladimir Gumenyuk (commander of the 1970 operation).

Beevor, Antony: Berlin: The Downfall 1945 (Penguin, 2002) – Chapter 19 and endnotes cite the original SMERSH report.

Fischer, Thomas: “Die Asche im Fluss – Die endgültige Beseitigung der Familie Goebbels” in Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft, 2015.