Warning: This article contains detailed descriptions of historical atrocities, genocide, and human suffering during the Holocaust, which may be distressing or triggering for some readers. Proceed with caution.

In the annals of human depravity, few figures embody the cold efficiency of industrialized genocide as starkly as Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss. As the longest-serving commandant of Auschwitz, the notorious Nazi concentration and extermination camp, Höss transformed a site of imprisonment into a mechanized factory of death. Under his oversight, more than one million people—primarily Jews, but also Roma, Poles, Soviet prisoners of war, and others—were systematically murdered in gas chambers and crematoria that he personally expanded and optimized. His innovations in mass killing, including the introduction of Zyklon B poison gas, marked a horrifying escalation in the Holocaust’s scale. Yet, Höss’s story culminates not in triumph but in reckoning: captured after the war, he faced trial and met his end on a gallows erected at the very site of his crimes.

Early Life and Path to Radicalization

Born on November 25, 1900, in Baden-Baden, Germany, Rudolf Höss grew up in a strict Catholic family dominated by his authoritarian father, a former army officer who instilled in him a rigid sense of duty and obedience. Defying his father’s wishes for him to enter the priesthood, young Höss volunteered for military service at age 15 during World War I, lying about his age to join the fray. He served on the Western and Eastern fronts, earning the Iron Cross for bravery and witnessing the horrors of trench warfare, which hardened his worldview.

The Treaty of Versailles and Germany’s defeat left Höss disillusioned and embittered. In the chaotic postwar years, he gravitated toward far-right paramilitary groups, including the Freikorps, where he participated in suppressing communist uprisings in the Ruhr and Baltic regions. His involvement in political violence escalated in 1923 when he was convicted of murdering a schoolteacher suspected of betraying a fellow nationalist. Sentenced to 10 years in prison, Höss served six before being released in a general amnesty in 1928. This period in prison further radicalized him, exposing him to antisemitic ideologies and a network of like-minded extremists.

Ascent in the Nazi Hierarchy

Upon release, Höss rejoined society as a farmer but soon sought purpose in the burgeoning Nazi movement. He joined the Nazi Party in 1934 and the SS (Schutzstaffel), the elite paramilitary organization under Heinrich Himmler. His loyalty and administrative skills propelled him upward: starting as a block leader at Dachau concentration camp, he rose through the ranks, learning the brutal mechanics of camp management under Theodor Eicke, the architect of the Nazi concentration camp system.

By 1938, Höss had become adjutant at Sachsenhausen camp, honing his expertise in prisoner control and forced labor. His promotion to SS-Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) reflected his growing stature. In May 1940, Himmler personally selected Höss to establish a new camp near the Polish town of Oświęcim (Auschwitz in German), initially intended for Polish political prisoners. What began as a modest facility would, under Höss’s command, evolve into the epicenter of the Final Solution.

The Industrialization of Death at Auschwitz

Höss served as Auschwitz’s commandant from 1940 to 1943, and briefly again in 1944. Tasked with expanding the camp, he oversaw its transformation into a sprawling complex encompassing Auschwitz I (the main camp), Auschwitz II-Birkenau (the extermination site), and Auschwitz III-Monowitz (a labor camp). By 1942, as the Nazis accelerated their genocide, Höss implemented “innovations” that turned murder into an assembly-line process.

Drawing from his visits to other camps like Treblinka, Höss introduced Zyklon B, a cyanide-based pesticide, as a more “efficient” alternative to carbon monoxide gassing. He supervised the construction of massive gas chambers disguised as shower rooms and crematoria capable of processing thousands of bodies daily. Victims arrived by train, were stripped of possessions, and herded into chambers where they suffocated in minutes. Bodies were then incinerated or buried in mass graves, with gold teeth extracted and hair shorn for industrial use. Höss’s deputy, figures like Erich Mußfeldt, assisted in these operations, but Höss bore direct responsibility for the industrial scale.

The numbers are staggering: Historians estimate that at least 1.1 million people perished at Auschwitz, with some figures reaching 2.5 million. Over 90% were Jews deported from across Europe. Höss himself later admitted in his autobiography, written while awaiting trial, that he witnessed the gassings and felt no remorse, viewing them as necessary orders. He even established a family villa adjacent to the camp, where his wife and children lived in relative luxury amid the surrounding horror—a chilling juxtaposition captured in later cultural depictions like the film The Zone of Interest.

In 1944, during the Hungarian deportations, Höss returned to Auschwitz to oversee the murder of over 400,000 Jews in mere months, dubbing it “Aktion Höss.” His methods set a blueprint for other extermination camps, embodying the Nazis’ bureaucratic banality of evil.

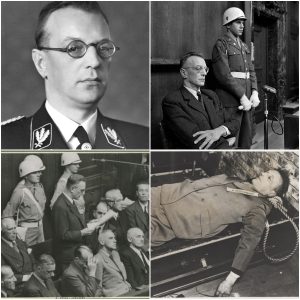

Capture, Trial, and the Weight of Testimony

As the Third Reich crumbled in 1945, Höss fled, assuming a false identity as a gardener named Franz Lang. He was captured by British forces in March 1946 near Flensburg, Germany, after his wife revealed his whereabouts under interrogation. Transferred to the Nuremberg Trials, Höss provided damning testimony against his superiors, detailing the mechanics of the Holocaust and estimating 2.5 million deaths at Auschwitz alone (later revised downward by historians).

Extradited to Poland, he stood trial before the Supreme National Tribunal in Warsaw from March 11 to April 2, 1947. Charged with crimes against humanity, Höss showed little emotion, claiming he was merely following orders. The court found him guilty on all counts, sentencing him to death. While in prison, he penned his memoir, Commandant of Auschwitz, offering a chilling insider’s view of the camp’s operations—though it has been criticized for downplaying his personal agency.

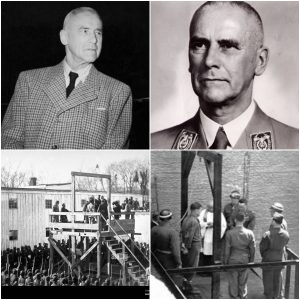

The Gallows’ Reckoning

On April 16, 1947, Rudolf Höss was hanged on a specially constructed gallows in the former Auschwitz I camp, mere steps from the gas chamber he had overseen. The execution, carried out by Polish authorities, symbolized poetic justice: the architect of mass death meeting his end at the site of his atrocities. Witnesses reported Höss remaining composed until the end, his last words a defiant “Heil Hitler.” His body was cremated, and the ashes scattered to prevent any shrine for neo-Nazis.

Legacy of Horror and Lessons Unforgotten

Rudolf Höss’s life serves as a grim reminder of how ordinary men can orchestrate extraordinary evil through obedience and efficiency. Auschwitz, under his command, became synonymous with the Holocaust’s mechanized terror, extinguishing over one million lives in a system designed for maximum lethality. Today, the site stands as a memorial and museum, educating millions about the perils of hatred and totalitarianism. Höss’s story underscores the importance of individual accountability in the face of systemic atrocity— a reckoning that came too late for his victims but endures as a warning for humanity.