Content Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of extreme violence, genocide, and atrocities committed during the Holocaust. Reader discretion is strongly advised; these accounts are based on historical testimonies and may cause significant distress.

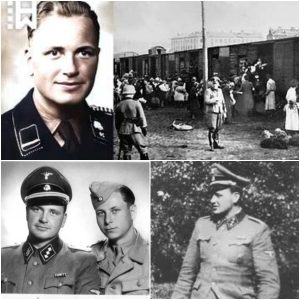

In the shadowed heart of Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the air reeked of ash and despair, one man’s name evoked terror even among the SS guards: Otto Moll. Born on March 4, 1915, in the rural village of Hohen Schönberg in the German Empire, Moll seemed an unremarkable figure in his youth—a trained gardener who joined the SS in 1935, playing in the battalion orchestra as a clarinetist. But a catastrophic truck accident in 1937 shattered his right eye, leaving him with a glass prosthetic and, more insidiously, a suspected frontal lobe injury that historians like Hans Schmid believe unleashed a cascade of psychopathic traits: dulled empathy, disinhibition, and a chilling lack of pity. Moll’s path to infamy was not merely a product of Nazi ideology; it was amplified by a fractured mind, transforming him from a peripheral enforcer into the “Father of the Crematoria”—a moniker whispered in horror by survivors who witnessed his “games” of sadistic cruelty.

Moll’s arrival at Auschwitz in May 1941 marked the beginning of his descent into the machinery of death. Initially tasked with digging mass graves at Sachsenhausen before his transfer, he quickly rose through the ranks of the Totenkopfverbände, the SS “Death’s Head” units. By 1942, as Rapportführer and chief overseer of the crematoria at Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Moll commanded the infernal operations that disposed of the camp’s human refuse. Under his watch, the crematoria—massive brick behemoths designed by Topf & Söhne engineers—churned through thousands of bodies daily. When the ovens couldn’t keep pace, Moll orchestrated open-air pyres, vast pits where fat from burning corpses fueled the flames in grotesque efficiency. He personally supervised the reactivation of a farmhouse gas chamber in 1944 to expedite the extermination of Hungarian Jews, ensuring the “Final Solution” ground on without interruption.

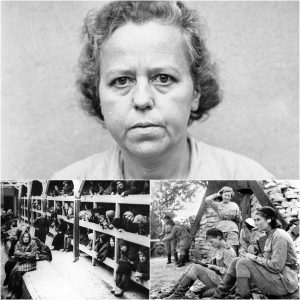

But Moll’s role extended far beyond logistics; he was the architect of agony. Eyewitness accounts from Sonderkommando prisoners—those forced to handle the dead—paint a portrait of a man who reveled in the visceral horror he inflicted. During the influx of Hungarian transports in 1944, when gas chambers proved too slow for smaller groups, Moll turned executions into macabre sport. He ordered prisoners shot at the edge of flaming pits, then had their bodies tossed in alive if they twitched. “It was like a game to him,” recalled one survivor, describing how Moll would laugh as he hurled emaciated children into the boiling fat of the pyres, their screams drowned by the roar of the fire. He beat Sonderkommando workers mercilessly for the slightest infraction, once dousing a group with petrol and setting them ablaze as punishment. Naked women were lined up and shot in the stomach, left to writhe in the flames while Moll watched with detached amusement. Children met even crueler fates: smashed against walls, thrown against electrified fences, or dangled by their feet before being swung into the inferno.

These were not impulsive acts but orchestrated spectacles—Moll’s “games” of unspeakable savagery. He set SS dogs on fleeing prisoners, forcing them to run toward barbed wire until electrocuted. In one documented instance, he hung victims upside down and burned them from the waist, prolonging their suffering for his entertainment. Even in quieter moments, Moll’s depravity shone through: he pilfered gold teeth, furs, and jewelry from the dead, extracting fillings with wire while joking about preparing for “lean years ahead.” His glass eye earned him the ironic nickname “Cyclops,” but it was his unblinking gaze on human suffering that branded him the “Butcher of Birkenau.” Estimates credit Moll with overseeing the cremation of 40,000 to 50,000 bodies in his sector alone, though the total death toll under his command likely reached hundreds of thousands, including a February 1945 massacre of 3,000 “dangerous” prisoners.

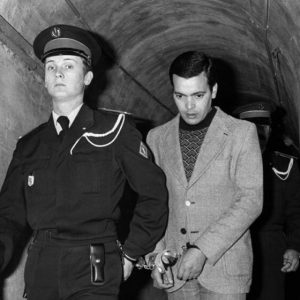

What twisted alchemy turned a gardener into this fire-keeper? Interrogations after his capture reveal a mind armored in denial yet laced with perverse pride. Surrendering to U.S. forces at Dachau in April 1945 after a grueling death march from Auschwitz, Moll faced the Dachau Trials in November of that year. Charged with shooting exhausted prisoners—26 murders confirmed by a Kapo witness—he was convicted and sentenced to hang. Under questioning, Moll deflected blame with bureaucratic precision: “I was never in charge of supervising the killings themselves… It’s possible that I shot some individuals, but the number was relatively small.” He insisted on Rudolf Höss’s presence—the Auschwitz commandant—to corroborate his “exemplary” conduct, claiming prisoners “respected” him for his soldierly demeanor. Yet cracks appeared: Moll admitted his “nerves cracked repeatedly” from the work, though he vehemently denied insanity, attributing it to stress rather than moral fracture.

Deeper probes into his psyche expose a sociopath molded by trauma and ideology. The 1937 accident, which blinded his eye and likely scarred his frontal lobe, may have eroded his inhibitions, fostering the sadism that Nazi doctrine then weaponized. Moll justified his horrors with the mantra “Befehl ist Befehl!”—an order is an order—echoing the regime’s dehumanizing ethos. But testimonies suggest more: a genuine thrill in the kill. Doctor Miklós Nyiszli, a forced pathologist at Auschwitz, dubbed him “the most insane murderer of the World War,” noting how Moll terrorized even fellow SS men with his excesses. He refused decorations for his “work,” not from shame, but because he deemed it unworthy of honor—implying a twisted humility amid his boasts. In one chilling aside, Moll mused he would cremate even Adolf Eichmann’s family if commanded, underscoring a loyalty that bordered on fanaticism. Heinrich Himmler reportedly praised Moll’s efficiency early on, only to later deem him “too brutal” for his uncontrolled sadism—a rare rebuke in a system built on terror. Yet Moll showed no remorse; in Nuremberg interviews, unlike the confessional Höss, he flatly denied Auschwitz atrocities, his mind a fortress of self-delusion.

On May 28, 1946, at Landsberg Prison, Otto Moll met his end on the gallows—hanged for crimes that scarred the soul of humanity. As the trapdoor dropped, the fire-keeper’s reign of flames extinguished, but the echoes of his savagery endure as a grim testament to how broken minds, empowered by evil, can consume worlds. Moll’s story is not just one of historical horror; it probes the abyss of the human psyche, reminding us that monsters are not born in vacuums but forged in the crucible of indifference and unchecked power. In understanding his mind—cold, fractured, and unyielding—we confront the fragility of our own.