Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of extreme violence, torture, and atrocities committed during the Holocaust. Reader discretion is strongly advised.

In the shadowed annals of Nazi horror, where the line between human and monster blurred into oblivion, few figures cast a longer, more chilling shadow than Kurt Franz. Amid the mechanized slaughter of the Holocaust, where the SS prided itself on ruthless efficiency, Franz stood out not for innovation in death, but for his gleeful, personal savagery. As commandant of the Treblinka extermination camp—one of Operation Reinhard’s deadliest killing grounds—he transformed a forest clearing in occupied Poland into a carnival of cruelty. Prisoners whispered of him as “Lalka,” the Doll, for his boyish face and impeccable uniform, but to those who survived his whims, he was the devil incarnate. Even his fellow SS officers, hardened by years of genocide, recoiled at his excesses, dubbing him a “real monster” among their own ranks of killers. This is the story of a man whose sadism didn’t just serve the Reich—it reveled in it, turning Treblinka into his private hell.

From Butcher’s Apprentice to SS Enforcer

Born on January 17, 1914, in Düsseldorf, Germany, Kurt Hubert Franz grew up in modest circumstances. His father, a merchant, died young, leaving his devout Catholic mother to remarry a fervent right-wing nationalist. Young Kurt absorbed the era’s brewing extremism, joining youth groups and the voluntary labor service before apprenticing as a butcher—a trade that, in hindsight, eerily foreshadowed his later vocation. He entered the Nazi Party in 1932, just as Hitler’s grip tightened, and was conscripted into the Wehrmacht in 1935. After honorable discharge in 1937, Franz volunteered for the SS-Totenkopfverbände, the “Death’s Head” units tasked with guarding concentration camps. Trained in Weimar, he was posted as a cook and block leader at Buchenwald, where he rose to the rank of Unterscharführer amid the camp’s early brutalities.

By late 1939, as World War II engulfed Europe, Franz was pulled into the Nazis’ covert euthanasia program, Action T4. Assigned as a cook at killing centers like Hartheim, Brandenburg, Grafeneck, and Sonnenstein, he witnessed—and likely participated in—the gassing of the disabled, the Reich’s grim prelude to the Final Solution. Promoted to Oberscharführer in April 1942, Franz transferred to the Lublin camp complex, serving briefly at Bełżec, the first Operation Reinhard extermination site. There, he honed his taste for terror amid the screams of the gassed. But it was Treblinka that would immortalize him as the SS’s own nightmare.

Descent into Treblinka: The Doll Who Danced with Death

In August 1942, as Operation Reinhard accelerated the extermination of Polish Jews, Franz arrived at Treblinka II, the death camp hidden in a pine forest near the village of the same name. Initially deputy to commandant Franz Stangl (no relation), he quickly asserted dominance. By mid-August 1943, following Stangl’s reassignment, Franz became Treblinka’s third and final commandant, ruling until the camp’s dismantlement in November. Under his watch, an estimated 700,000 to 900,000 Jews—mostly from Warsaw, Białystok, and other ghettos—were murdered in gas chambers disguised as showers, their bodies burned in open pits or crematoria.

Franz’s reign was no mere administrative post; it was a symphony of sadism. Nicknamed “Lalka” (Yiddish for “doll”) for his cherubic features and dapper attire, he patrolled the camp on horseback, a St. Bernard named Barry at his side. The dog, trained to maul on command—”Mensch, faß den Hund!” (“Man, sic ’em, dog!”)—targeted prisoners’ genitals, buttocks, or abdomens, tearing flesh while Franz watched impassively. Barry was docile in the commandant’s absence, but his presence signaled doom. Franz, a former boxer, turned Jewish prisoners into human punching bags, pummeling their heads until they collapsed—sometimes concealing a pistol in his glove to deliver a fatal shot mid-blow.

His cruelties were as inventive as they were capricious. He forced naked prisoners to dance the “Treblinka Waltz” under threat of whips or bullets, beating them with leather straps until skin split. Bearded men were made to hold beer bottles to their chins as “tests of God,” with Franz firing his rifle to shatter the glass—and often the jaw beneath. Children were his particular fixation; survivor Abraham Goldfarb testified that Franz would “play” with Jewish boys and girls, tossing them in the air and catching them, cooing that they were “all headed for heaven” before marching them to the gas chambers. In one grotesque episode, guards under his orders sliced open pregnant women’s bellies to crush fetuses with rifle butts, all while Franz looked on. He decorated his office with victims’ skulls and human skin lampshades, mementos of his “beautiful times.” Witnesses estimated he personally killed at least one prisoner daily, often for the slightest infraction—a dropped tool, a hesitant step.

Franz even composed a camp anthem, a jaunty tune borrowed from Buchenwald and set to lyrics he penned: “Looking squarely ahead, brave and joyous, at the world. The squads march to work. All that matters to us now is Treblinka…” Sung by prisoner orchestras to drown out the cries from the gas chambers, it underscored his delusion of Treblinka as a twisted idyll. Among the SS, his bloodlust was legendary; colleagues like Josef Hirtreiter, another Treblinka guard later sentenced to life, reportedly shuddered at Franz’s “unnecessary” excesses. To them, genocide was duty; to Franz, it was delight.

The Revolt, the Rubble, and the Reckoning

Franz’s overconfidence nearly undid him. On August 2, 1943, while swimming in the Bug River with Barry, he left security lax—sparking the Treblinka uprising. Prisoners armed with smuggled weapons stormed the camp, burning barracks and killing 20-30 guards before fleeing into the woods. Nearly 300 escaped, though most were recaptured and killed. Franz, unfazed, suppressed the revolt and continued gassings at reduced capacity, processing survivors from the Białystok ghetto until August 19.

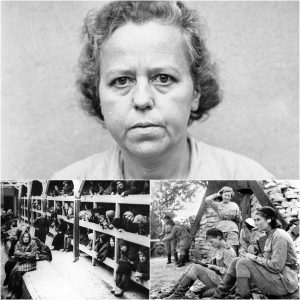

By September, orders came to erase Treblinka’s crimes. Franz oversaw the demolition, using SS men, Ukrainian auxiliaries, and 100 Jewish Sonderkommandos to plow under mass graves, scatter ashes, and plant lupins over the killing fields. The last prisoners were shot and cremated in November 1943; some were shipped to Sobibór for further labor. Franz then joined Odilo Globocnik in Trieste, Italy, hunting partisans and Jews until a 1944 wounding sidelined him to railway security.

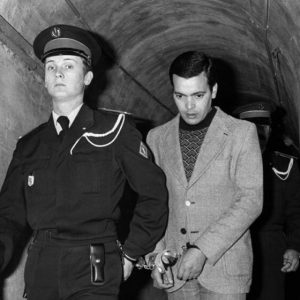

War’s end found Franz in Allied custody, but he slipped away, posing as a common laborer on Düsseldorf bridges until 1949. He then worked as a cook—irony undimmed—until his arrest on December 2, 1959. A search of his home uncovered a photo album titled Schöne Zeiten (“Beautiful Times”), filled with snapshots of Treblinka: Franz posing jovially with guards, prisoners mid-parade, even a mock railway station built to lull arrivals into complacency.

The First Treblinka Trial, from October 1964 to August 1965 in Düsseldorf, laid bare his legacy. Tried alongside nine other ex-SS men, Franz denied everything—killings, dog attacks, even beatings—claiming he was “just following orders.” Survivor testimonies painted a damning portrait: over 100 witnesses detailed his murders, from the casual shootings to the orchestrated tortures. The court convicted him on 35 counts of murder (139 victims named), collective murder of at least 300,000, and attempted murder, sentencing him to life imprisonment on September 3, 1965. The verdict thundered: “A large part of the streams of blood and tears that flowed in Treblinka can be attributed to him alone.” Co-defendants like Hirtreiter and Arthur Matthes also drew life terms; others received lesser sentences.

A Monster’s Quiet End

Franz served 28 years behind bars before release in 1993 on health grounds—blind, infirm, unrepentant. He died on July 4, 1998, in Wuppertal, Germany, at age 84, his passing noted only in Holocaust archives. No apologies, no reflections; just the silence of a man who once filled Treblinka with screams.

Kurt Franz was no aberration in the Nazi machine—he was its sharpened edge, the sadist who made efficiency feel personal. To the SS, architects of industrialized death, he was the nightmare they couldn’t control: a “real monster” whose brutality shamed even their own. In remembering him, we confront not just one man’s evil, but the fragile veil between order and abyss that Treblinka tore away. Lest we forget, the Doll’s beautiful times were humanity’s darkest hour.